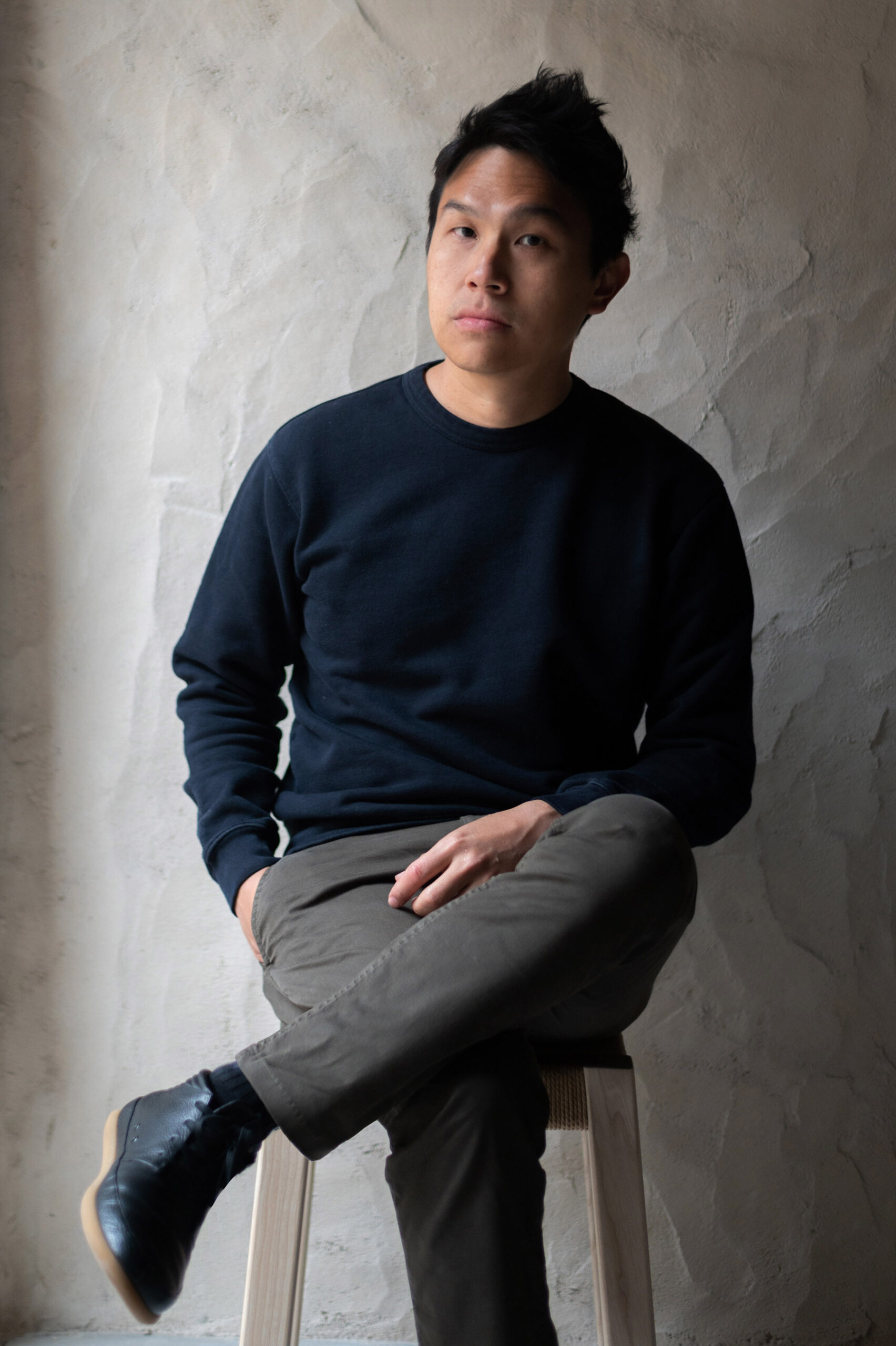

In the latest edition of our interview series, we once again dive into the world of minimalist aesthetics. In inspiring conversations with creative minds from the fields of architecture, design, and art, we explore how they are guided by their vision and how they express it in their works. Along the way, they provide us with interesting insights into their creative process and reveal how they perceive and shape the world. This time, I had the pleasure of having an inspiring conversation with designer Gabriel Tan.

The Singapore-born designer Gabriel Tan, now based in Porto, combines the tradition of craftsmanship with the demands of modern design in his sleek creations. His design aesthetic is informed by a minimalist perspective, combined with a deep appreciation for organic forms and artisanal details. He launched his own design practice in 2016 and the brand Origin Made in 2018, and has designed products for some of the world’s most recognized brands, including B&B Italia and Herman Miller.

In today’s interview with Gabriel, we learn about his unique design philosophy and creative process. We delve deeper into how he approaches his projects and values the relationship between designers and craftsmen.

Gabriel, it’s a pleasure to talk to you today about you and your work. Please tell us how you would describe your personal design philosophy and aesthetic? How has it developed over the course of your career?

I believe that great design emerges from the synergy of open-minded, positive, and collaborative individuals. For me, understanding the people behind a brand is far more crucial than the brand itself – after all, a brand’s story can always be rewritten, but the essence of its creators remains.

Aesthetically, I find myself drawn to minimalism, yet I’m not a purist. I have a deep appreciation for soft, organic forms that bring ‘warmth’ to clean lines. My work often walks a tightrope between expressiveness and restraint, with the balance shifting depending on the project at hand.

Looking back, I can see an evolution in my aesthetic. In the early days of my career, I gravitated towards lightness and delicate lines – think of the Ariake chair and Sky Ladder shelf I designed for Ariake in 2017. Over time, as I have grown as a designer, my designs have also evolved. This change can be seen in more recent works like the Luva sofa and Cyclade tables for Herman Miller, launched last year, which showcase a bolder, more expressive approach to form and materiality.

In an interview, you once said that design is not just a job for you, but an essential part of your life. Considering your diverse projects and roles, how do you find balance while maintaining your creativity and enthusiasm?

I draw a parallel between design and professional sports – in order to better my design, I have to push myself out of my comfort zone and beyond my limits, and thereafter set a new limit to work towards, to break that barrier again – a cycle of perpetual growth and challenge. Just like how sport is for sportsmen, it’s not possible to separate design from life, but the great thing about design is that I can do this professionally until I’m 95, for as long as I’m alive, and not stop at 35.

Of course, balance is important, and I disconnect by exercising or spending time with my family. I have two young boys whom I adore, so if I do need to work late, the limit is when it’s time for bedtime stories. Starting a family helped me find balance. If not, I could easily go on working till dawn if I were “on to something”.

My work often walks a tightrope between expressiveness and restraint, with the balance shifting depending on the project at hand.

You launched Origin Made in 2018, to “put the artisan and the process of making in focus, where the designer is the secondary protagonist instead”. In your opinion, how important is the relationship between designers and artisans?

Designers cannot do everything, but the marketing engine of most brands has made us into the faces behind the products. For products that are machine-made, there is the engineer who is the invisible protagonist and for products that are handmade, there is the artisan. I have worked with many great engineers and artisans throughout my career and without them my products could not have been realized. The relationship between a collaborating designer and artisan has to be one of mutual respect, openness and cross-learning for it to work.

Origin Made is, in many ways, my love letter to these unsung heroes of design. It’s an attempt to shift the narrative, to give artisans the recognition they deserve – a face, a voice, to be seen and heard. I believe this transparency enriches the consumer experience too, allowing people to fully appreciate the journey of the objects they bring into their homes and their lives.

How do you personally define good design? Do you think design can be art?

Good design strikes a balance between beauty and utility/ usefulness – akin to a dance of form and function. But I also believe that design can be just about the ‘art’. Even when an object lacks a traditional function, it can still serve a profound purpose by elevating our emotional well-being and transforming the atmosphere around us.

This reminds me of the writings of Bruno Munari in “Design as Art”, where he said that the profession of the designer was evolved from that of the artist, who began making useful art for the people, and how it is important to preserve this artistic essence in modern design practice, not lose the ‘art’ in the design profession today.

I believe design serves as a powerful medium to elevate and share rare or lesser-known cultural crafts with a global audience.

Running a successful design studio and brand requires not only a lot of creativity but also entrepreneurial skills. What entrepreneurial challenges have you encountered along the way, and how did you overcome them?

In the early days, I wore every hat imaginable – from web designer to accountant, from client liaison to social media manager. While this hands-on approach gave me invaluable insights into every facet of the business, I soon realized it was constraining my creative output. The turning point came when I decided to invest in talented individuals to manage these various aspects of the business. This strategic decision proved transformative. The mental space and time it freed up allowed my creativity to flourish in ways I had not anticipated. It was a powerful lesson in the value of delegation and the importance of focusing on one’s core strengths.

Another more personal challenge was overcoming my introverted nature in an industry that thrives on face-to-face connections. Design is inherently social, requiring constant interaction with clients, collaborators, and peers. Pushing myself out of my comfort zone became a daily practice. Over time, I have learned to embrace these interactions, seeing them not as obstacles but as opportunities for growth and inspiration.

You once said that design is a dynamically evolving process for you – take us through this process. What are the first steps when you work on a new project and what role does your intuition play in it?

The first step I take is usually to visit and connect with the people I am collaborating with. To see their headquarters, their factories, or even their homes. Understanding their motivations, and what they desire for their project is important, but even more so is observing what they have not realized they might need. Ariake was a good example of this. Had I jumped right into their email brief of designing 3 to 4 products targeting the Singapore market for their two parent companies, Ariake would not have been born.

Instead, I spent 2 days visiting their factories in Saga, having meals with the owners and walking around their town. This led me to want to show the world what these two factories from a small town in southern Japan had to offer – and to tell the story in the right way, we needed a completely new brand and a new mix of designers and products. Intuition is a large part of it, but only with enough information from an in-person experience. Without that direct interaction, intuition alone would not have led me to the same result.

Over the course of your career, you have also worked with renowned brands such as Herman Miller, B&B Italia, Audo Copenhagen (formerly Menu), among others. How does working with such partners influence your personal design practice? How do you navigate the balancing act between your own creative vision and the requirements and identities of these brands?

I think it gives everyone in the studio a confidence boost to work with such renowned partners. Personally, I was in awe when I first visited the headquarters and factories of B&B Italia and Herman Miller, but at the same time, I knew I had to not let that sense of admiration overwhelm me. Because when you collaborate with a brand, you need to bring something that they do not yet have to the table.

It is not about designing to fit into the style they are known for because the only reason they could be interested in a new designer is because of one’s fresh ideas or aesthetics so that the brand can evolve. I think the best collaboration is when it is a mutual evolution, where the designer and the collaborating brand both push themselves out of their comfort zone. That said, I do think it’s important to understand the brand’s history, archival and existing products so that the result is a philosophical and/or aesthetic evolution and not a total disconnection from what they were doing before.

To what extent do you think design can act as a bridge between different cultures? Do you have specific examples from your work where design has promoted cultural exchange?

Definitely! I believe design serves as a powerful medium to elevate and share rare or lesser-known cultural crafts with a global audience.

In the case of the Charred Vases, I designed for Origin Made, I collaborated with master potter João Lourenço who is one of the few craftsmen in Portugal who are still making “Barro Preto” – an ancient Portuguese technique of firing black ceramics in a soil pit with firewood. When I first visited his atelier and saw this beautiful craft, I immediately recognized its potential to go beyond local borders. I designed five unconventional forms that were radically different from traditional “Barro Preto” vases—or any vases, for that matter. The result was a fresh take on this ancient technique, and today the Charred Vases are owned by people all over the world, making it Origin Made’s best-selling collection.

And finally, how do you see yourself and your work in the future? Are there certain projects, techniques or materials you haven’t worked with yet that you would like to explore?

Looking ahead, I see ourselves continuing our design work for a selective number of international brands while growing Origin Made into a brand that stands at the crossroads of design, art and crafts – not only Portuguese crafts but crafts from around the world. We started with Spain this year (with the Barco and Calabash Basket Sculptures in collaboration with Spanish weaver Idoia Cuesta).

As for new frontiers for me and the team, I would love to work on transportation and technology projects, such as designing cabin interiors of trains or aircrafts, and even venturing into consumer electronics. I know that there are specialist design firms for these types of projects, but I believe we can offer a unique viewpoint that blends aesthetics with human experience, especially when working in close collaboration with engineers, technologists and the relevant specialists.

Thank you very much, Gabriel!

More about Gabriel Tan

https://www.gabriel-tan.com/

https://www.instagram.com/gabrieltandesign/