There are so many exciting aspects of abstract, minimalist art to explore and the theme of repetition is definitely one of them. For some it may seem boring and monotonous, but for others it reveals a deep, meditative quality. In art with a minimalist aesthetic, it becomes a central element in the works of some, an artistic stance that goes far beyond what we see. Repetitive brush strokes, lines, or shapes merge into a visual pattern that speaks a unique language. So what prompted artists both then and now to use this stylistic device? What effect does it have on the viewer, and what does the artist want to achieve with it? That’s what I want to explore today.

Repetition is not a new phenomenon; rather, it runs like a red thread through the entire history of art. Since the earliest human drawings, artists have used repetition as a means of creating rhythm, patterns and structure in their works. At the beginning of the 20th century, however, there was a turning point in the visual arts. Artists started to use their art as a tool for their explorative investigations, and repetition became one way to represent these aspects.

One of the first artists of the 20th century to use repetition as an artistic medium was the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși. His work “Endless Column” from 1918 shows a harmonious pattern of repeating rhomboid modules strung together. These successive modules form a kind of column that could theoretically be continued into infinity. The significance of the repetition in the “Endless Column” is therefore both conceptual and visual: it creates the impression of continuity, infinity and rhythmic movement.1 Brâncuși took up the motif of the column several times in his life and created different versions of the sculpture. The best known is the famous 98-meter-high Endless Column in Tîrgu-Jiu, Romania.

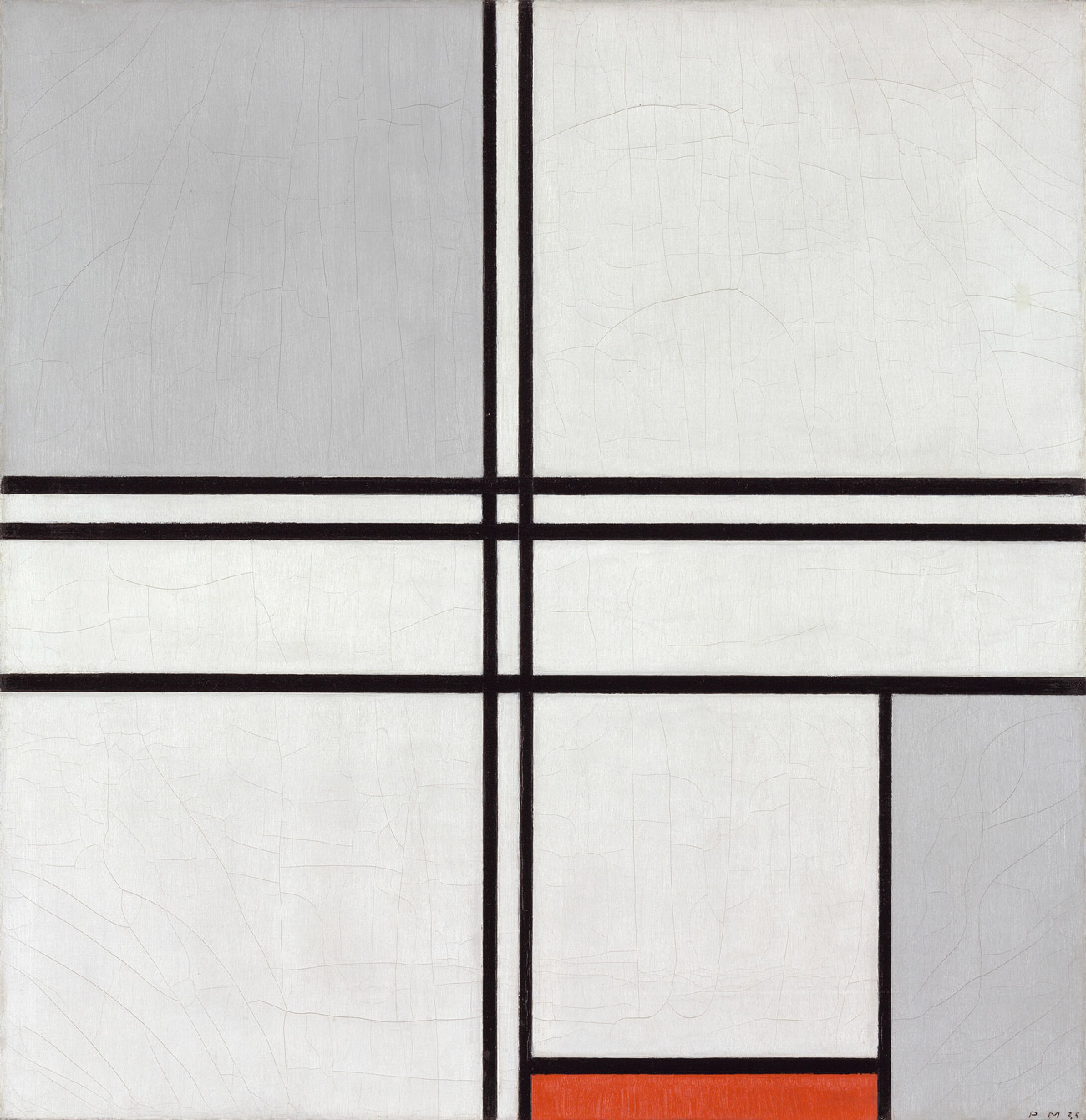

Irregular repetitions can be found in the works of Piet Mondrian, who became more abstract and minimalist in his expression after the First World War. Around 1916, he turned away from the representational depiction of the world and since then, has reduced his works to their most basic forms and structures. He used repetition to structure his paintings, as can be seen in his work “Composition (No. 1) Gray-Red” from 1935 (fig. 1), for example. He believed that rhythm could be expressed not only in music and dance, but also in painting by consciously repeating and arranging shapes and colors.2

Repetition as an important element in Minimal Art

In the middle of the 20th century, artists such as Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Carl Andre and Frank Stella began to use repetition as an artistic tool to draw attention away from metaphorical meanings and towards the physical presence of the artwork itself.

The best-known example of this is Donald Judd’s ‘Stacks‘: In this series of objects, Judd stacked a series of rectangular modules on top of each other on the wall, keeping constant distances between each box. He preferred uniform, repetitive forms that were not intended to suggest or impose any symbolic meaning. Judd wanted his work to have its own presence in “real space” without referring to metaphorical or symbolic content. By repeating the same elements over and over again, he created objects in which no particular element forms the visual or compositional focus. The entire object should be seen as a unified, indistinguishable whole.3,4

Thus, the conceptual attitude behind the repetition not only served the aesthetic experience of the work, but primarily emphasized the object itself. Each artist in the movement brought different conceptual considerations to their work. Niele Toroni, for example, an early representative of European minimalist painting, has exclusively used repetitive brushstrokes in his ‘empreintes‘ since 1966.5

Carl Andre, on the other hand, created simple, geometric patterns, often composed of repeated, modular units such as metal plates, pieces of wood or bricks. He was inspired by Constantin Brâncuși’s Endless Column, among other things.6 The arrangement of these elements was always well-thought-out and followed a certain rhythm. This was intended to influence the perception of the work and its relationship to the space in which it was presented. The viewer is thus involved in his work and is invited to explore and experience the artwork not only visually, but also through physical movement in space. And Sol LeWitt conceived minimalist works from repetitive geometric forms. He followed a methodical and planned approach aimed at minimizing the artist’s subjective influence.7

Repetition thus served as a central tool for artists in Minimal Art to convey their conceptual thoughts and ideas. It reflects their efforts to emphasize the autonomy of their works and to draw attention to the artwork as a whole. By creating a direct, unmediated experience between viewer and object, artists of the movement sought to minimize subjective influences and foster a new, unadulterated relationship with art.

Repetition as a spiritual, meditative act

However, many artists did not use this stylistic device for this purpose only. Instead, they used repetition to explore introspective and spiritual themes or as part of a meditative process while painting.

Repetition played a central role in Agnes Martin’s works, which are often classified as Minimal Art due to their reduced aesthetic. Her grids and geometric compositions appear austere, sober and restrained, but she wanted to “express beauty, happiness and innocence” in these repetitive patterns.8

Far from being sober or restrained, the pencilled lines show subtle variations in stroke, intensity and tone. Martin’s approach transforms repetition into a spiritual exercise with which she attempts to explore and depict universal truths and states of being. She found her inspiration in the teachings of Taoism and Zen9. With an empty mind – free of ideas and the ego – she created her works by concentrating entirely on the act of painting.10

Martin’s approach emphasizes a dimension of art with a minimalist aesthetic that, I think, is unfortunately often overlooked: the potential for a spiritual or meditative experience. Her art teaches us that a space for deeper thoughts and feelings can exist in silence, simplicity and repetition. Perhaps this is the reason Martin refused to be associated with the Minimal Art movement, as her art goes beyond the mere reduction of form and content.

I would like [my pictures] to represent beauty, innocence and happiness.

Agnes Martin

Like Martin, the artists of the Dansaekhwa movement saw repetition less as a means of visual expression and more as a meditative process. Dansaekhwa, also known as Tansaekhwa, was an art movement that originated in South Korea in the 1970s. The term itself can be roughly translated as “monochrome painting“. Artists such as Lee Ufan, Park Seo-Bo and Yun Hyong-Keun are among the most important representatives of this movement. The meditative process in the creation of their works – often characterized by the continuous incision of lines, hatching or the repetitive application and removal of paint – was a core aspect of their artistic practice.

Through this repetition, they shifted the focus from the artwork to the act of painting itself. Park Seo-Bo said: “In fact, the art of Dansaekhwa is not so much about the color as it is about the essence of the action itself—the repetitive gestures that empty and cultivate the painter’s mind.”11

In his “Ecriture” series, Park opened himself up to the process of self-knowledge and letting go by repeating graphite marks and then painting over them. He saw repetition as a way of freeing himself from past experiences and discovering his creativity.12 Lee Ufan on the other hand, who is known for his minimalist and meditative approaches to painting and sculpture, uses repetition as a philosophical act. His works “From Line” and “From Point”, in particular, are characterized by repeated brushstrokes. In contrast to his American Minimal Art colleagues, Lee used repetition as a way to create resonance and dialog between the artist, the work and empty space.13

Repetition as a personal practice in creative expression

This kind of meditative and philosophical repetition thus served the artists not only as a creative means, but also as a path to a deeper understanding. For Martin, Park, Lee and many other artists who saw repetition as an integral part of their art, this simple act became a deep, personal practice. A practice with complex, individual meanings.

In his minimalist works, the introspective Canadian artist Alexander Jowett (fig. 2) uses the repetition of lines as a central theme of depicting open, meditative spaces. Inspired by Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason” and his many travels, he explores the philosophical concepts of perception and existence in them. By drawing the lines in a slow, mindful process, he aims to incorporate the meditative aspects of his work into the paintings.14

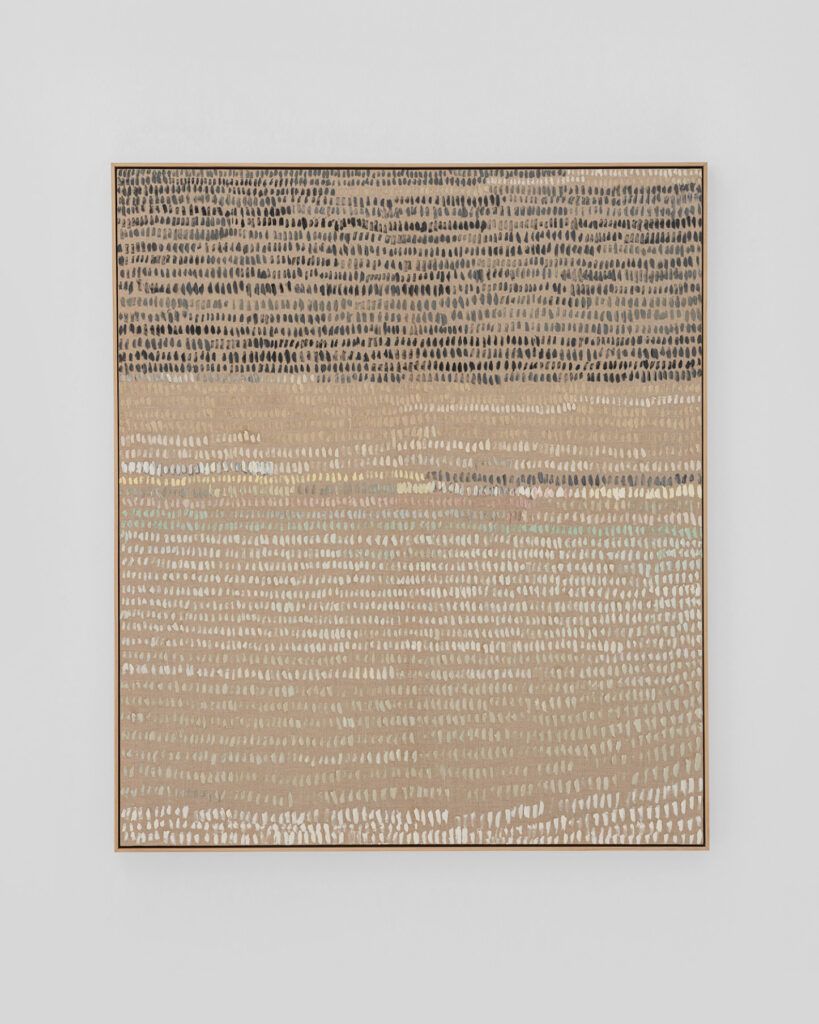

Equally, for the Spanish artist Maria Yelletisch (fig. 3), repetition is not merely an aesthetic aspect of her work. Through the repeated movements during her creative process, she reaches a state of flow, which allows her to deeply immerse herself in her own world of thoughts and emotions. Each stroke becomes a sort of rhythmic meditation, creating a profound connection between her mind, the artwork, and the emotions contained within. Repetition enables her to develop a visual language that reveals both a spiritual and a contemplative dimension of her artistic expression.15

Whatever their motivations, repetitive activities require you to focus on the present and direct all your attention to the action itself. This form of focused attention is an important core aspect of mindfulness practice. It can calm the mind and create a deeper connection with oneself. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why works by artists such as Agnes Martin, Park Seo-Bo, Lee Ufan, Alexander Jowett or Maria Yelletisch have such a calming effect?

It is therefore worth pausing the next time you look at such a painting and allowing it to have a more intensive effect on you. Who knows what it will reveal to you?

Further Reading / Resources

- https://www.moma.org/collection/works/81729

- https://www.kunstsammlung.de/de/mondrian/trace04/

- https://notations.aboutdrawing.org/category/donald-judd/

- https://ropac.net/ko/news/335-donald-judd/

- https://www.artforum.com/events/niele-toroni-211357/

- https://galeriegretameert.com/exhibitions/carl-andre/

- https://lornashieldsart.wordpress.com/2013/04/17/discussing-sol-lewitt/

- https://www.guggenheim.org/exhibition/agnes-martin

- https://www.guggenheim.org/teaching-materials/agnes-martin

- https://www.theartblog.org/2016/11/solitary-lines-agnes-martin-at-the-guggenheim/

- https://artasiapacific.com/issue/park-seo-bo-disciple-of-nature?locale=en

- https://parkseobofoundation.org/story/?idx=10438869&bmode=view

- https://artmap.com/schwarzwaelder/exhibition/lee-ufan-2007

- https://www.aesence.com/a-conversation-with-alexander-jowett/

- https://www.aesence.com/a-conversation-with-maria-yelletisch/