In the latest edition of our interview series, we once again dive into the world of minimalist aesthetics. In inspiring conversations with creative minds from the fields of architecture, design, and art, we explore how they are guided by their vision and how they express it in their works. Along the way, they provide us with interesting insights into their creative process and reveal how they perceive and shape the world. This time, I had the pleasure of having an inspiring conversation with Irish artist David Quinn.

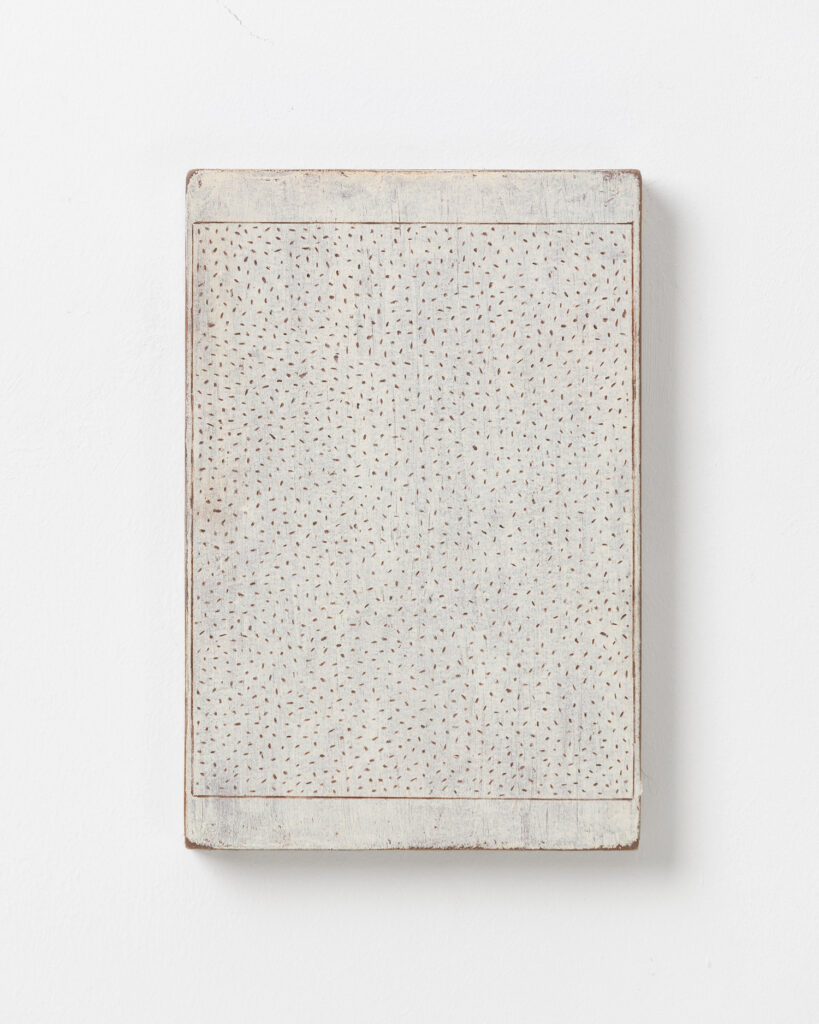

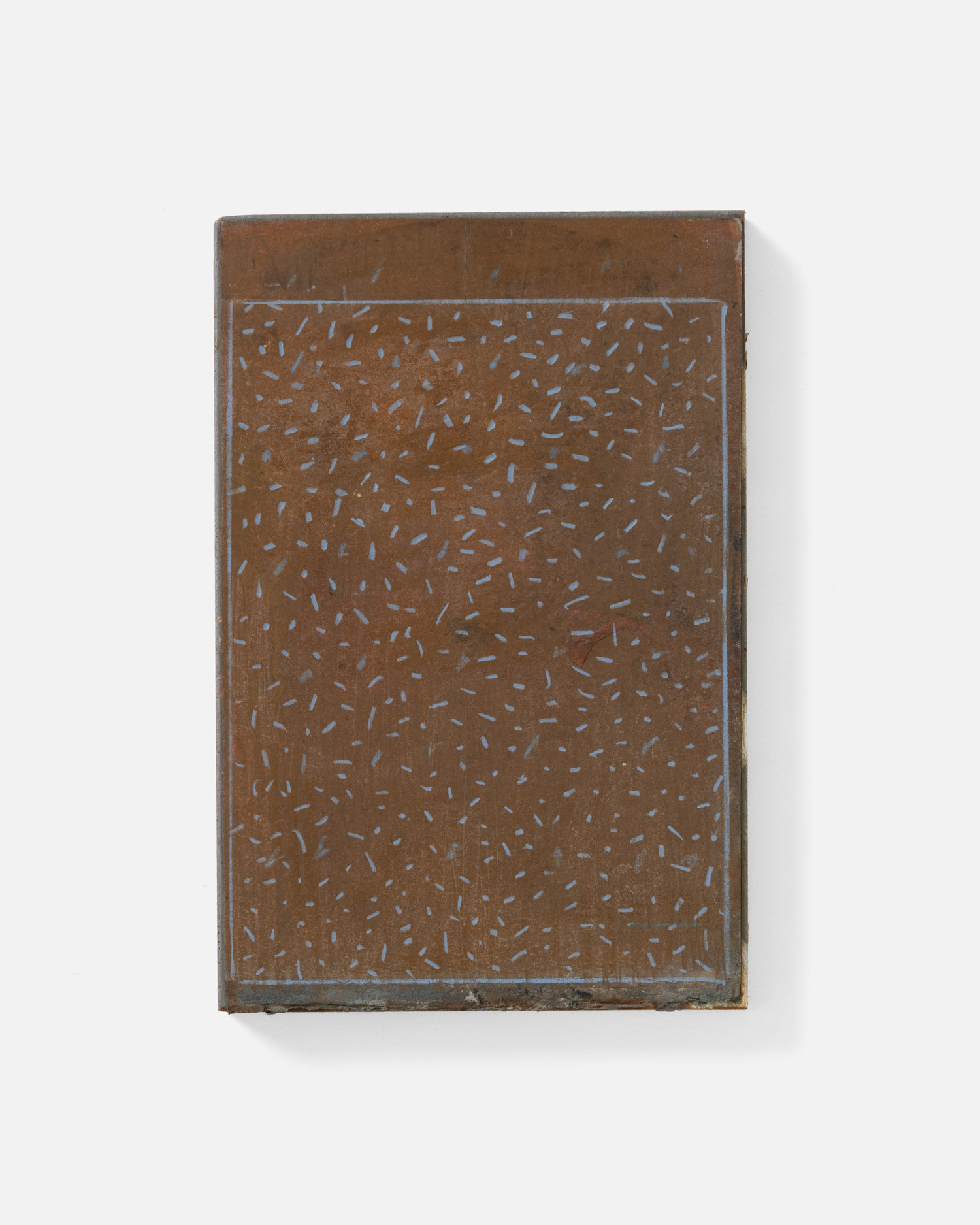

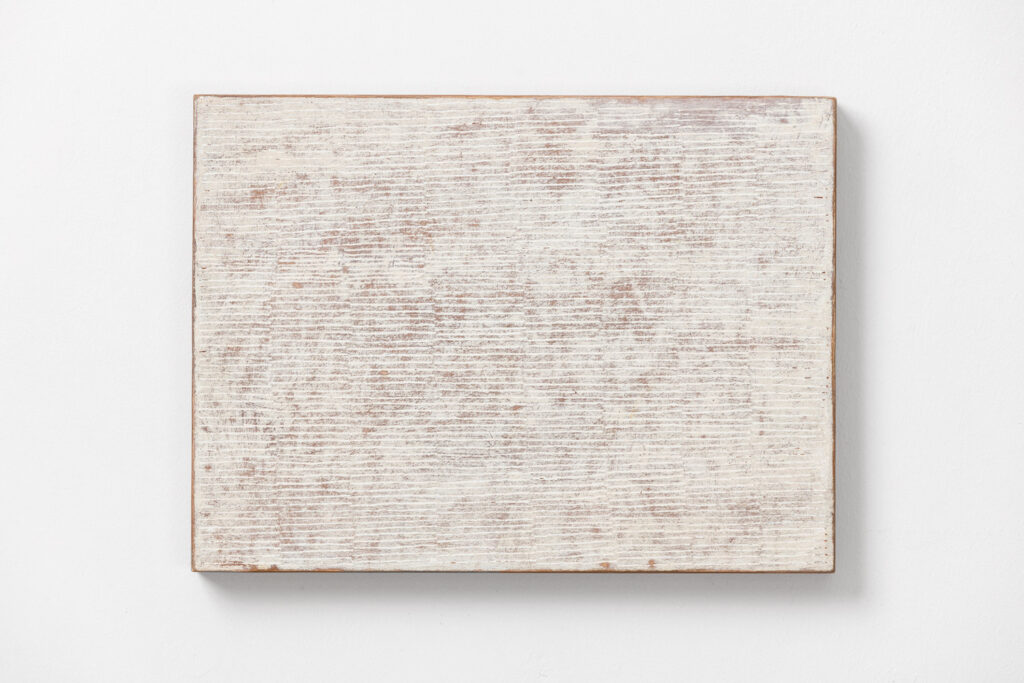

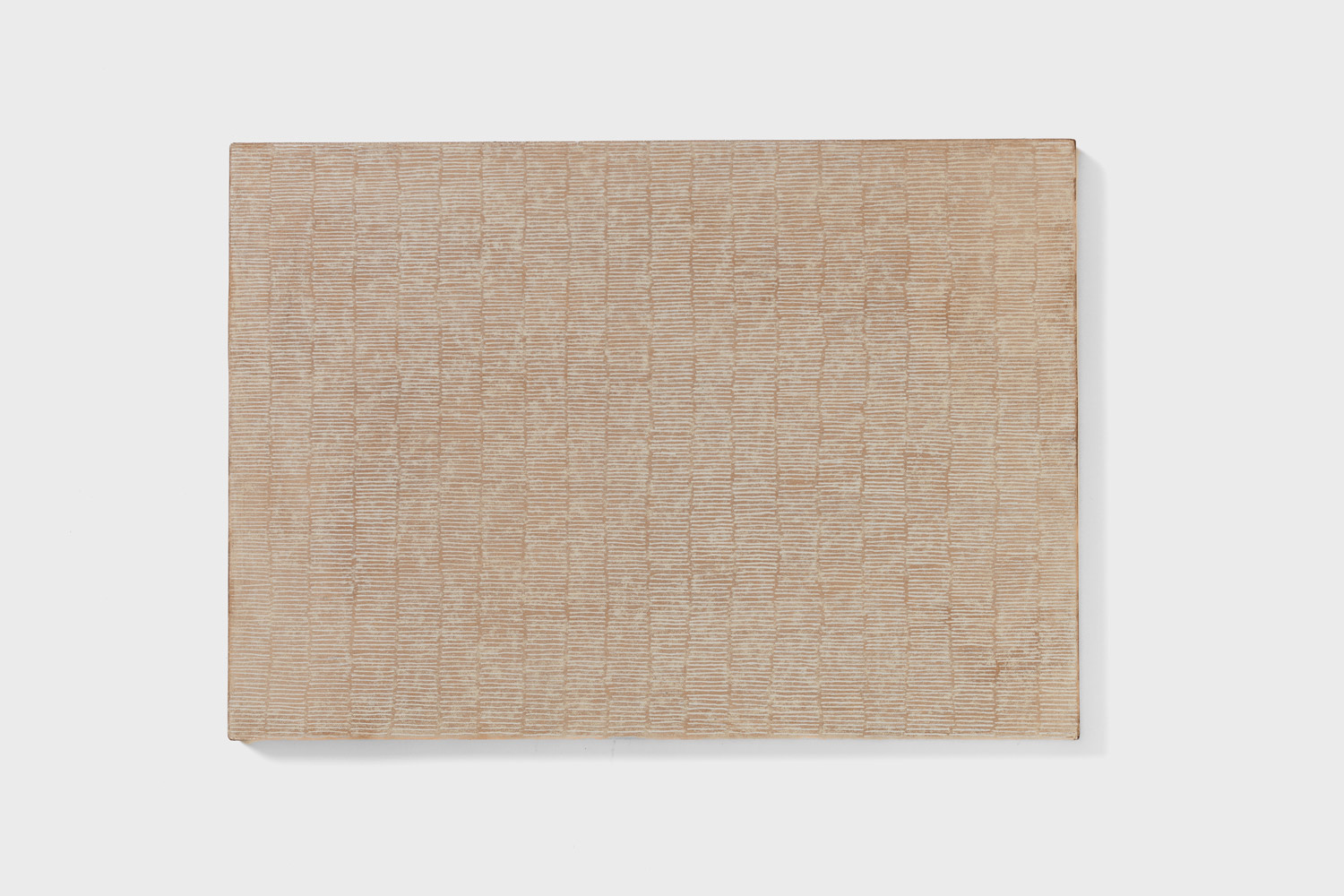

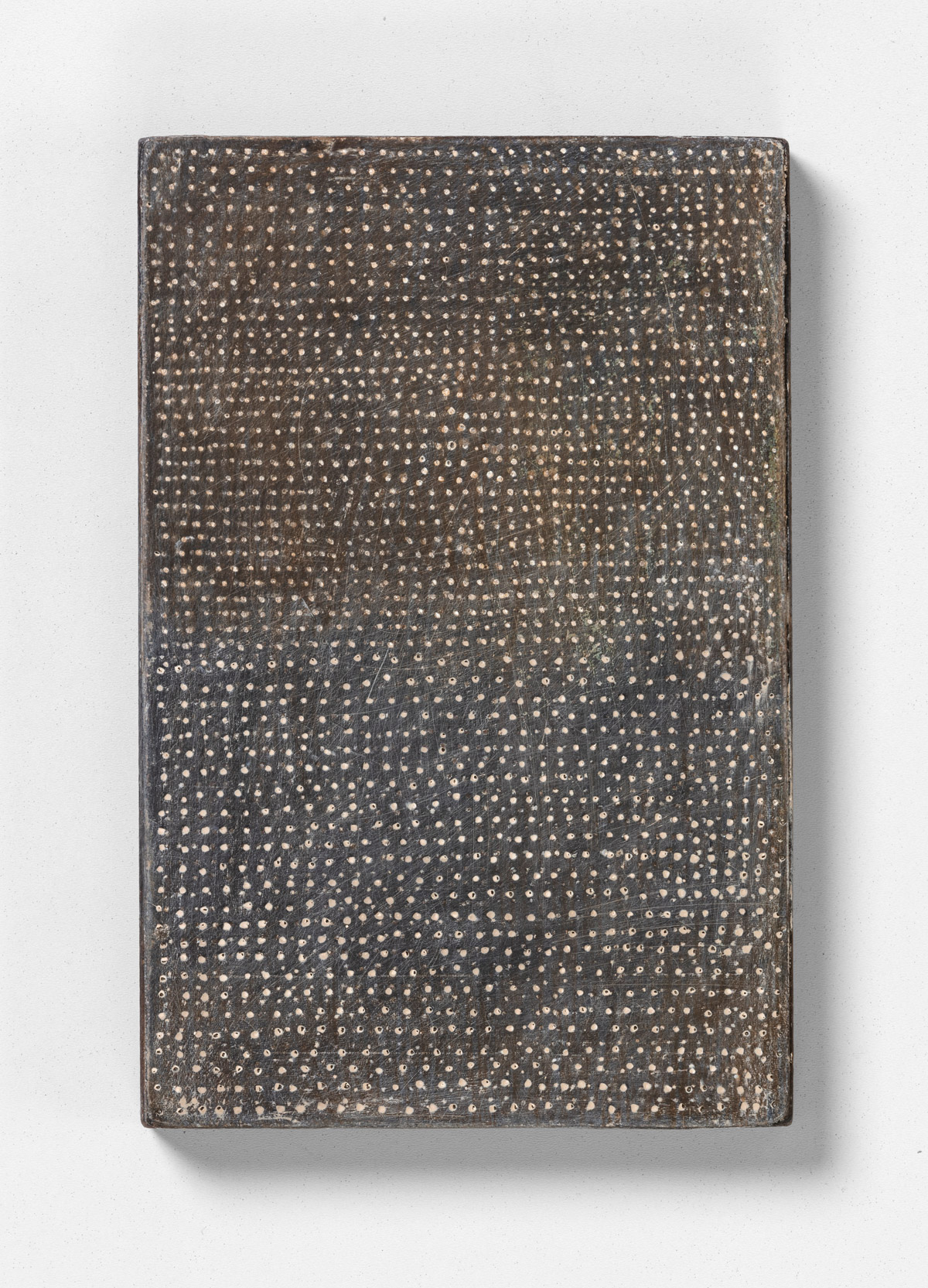

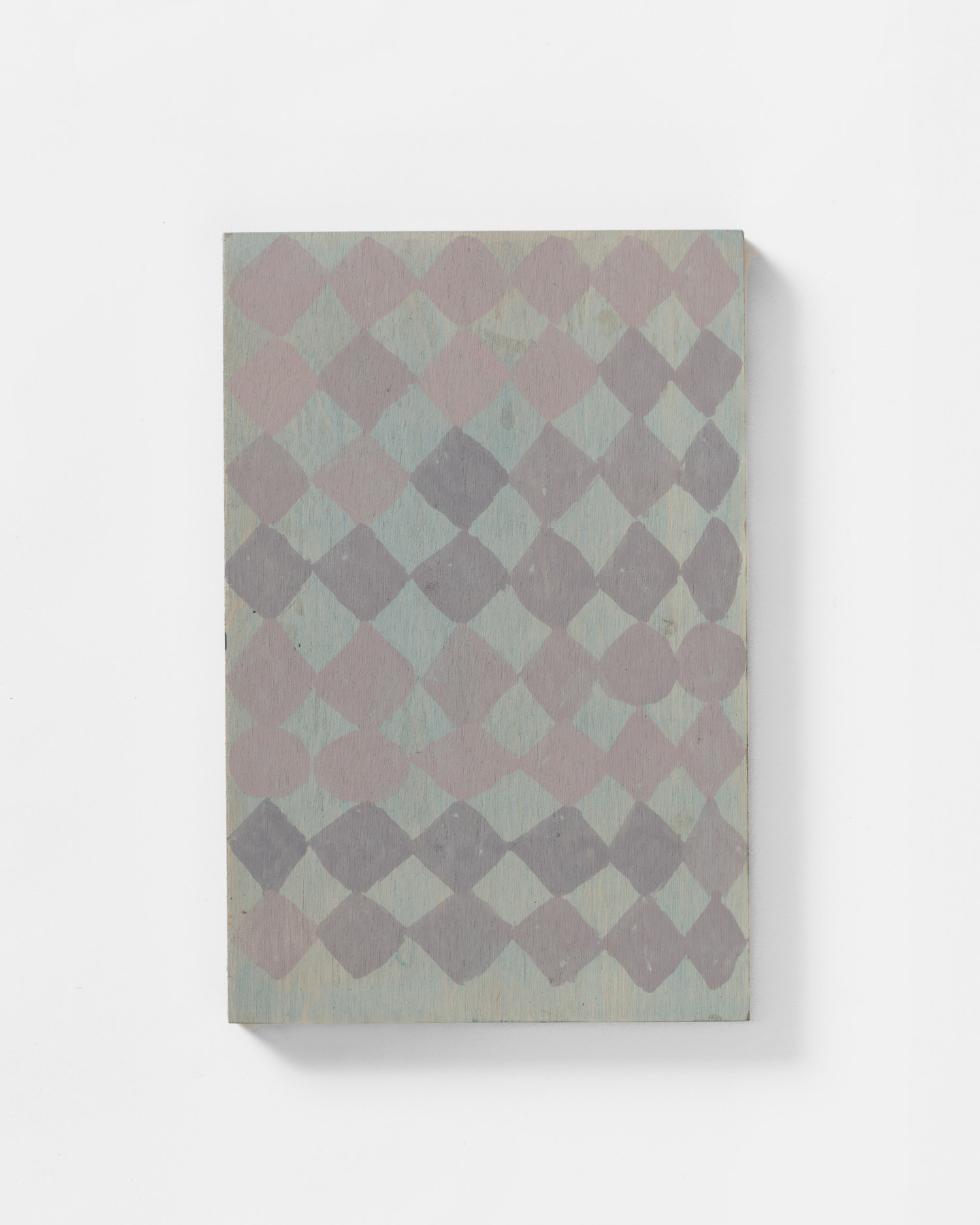

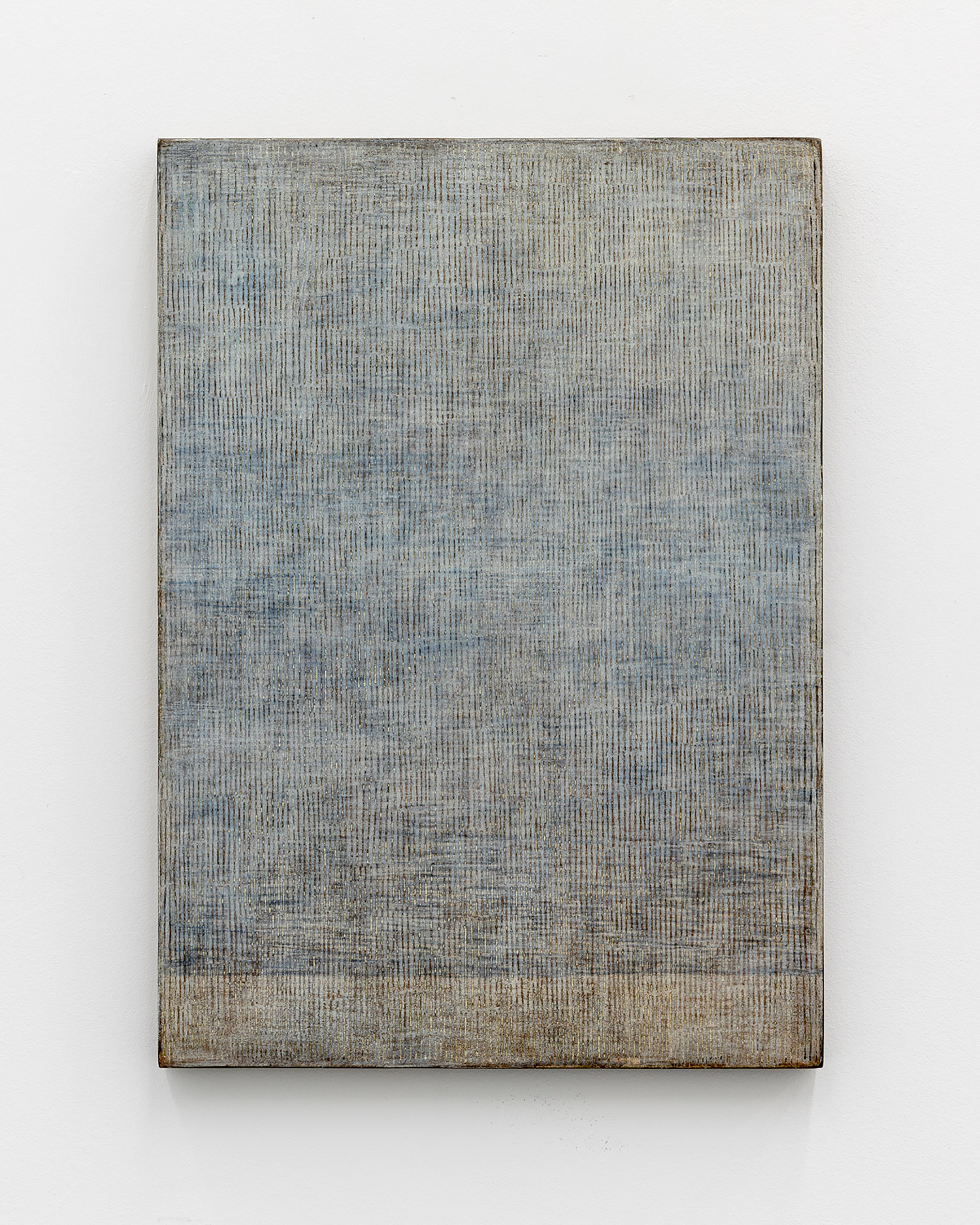

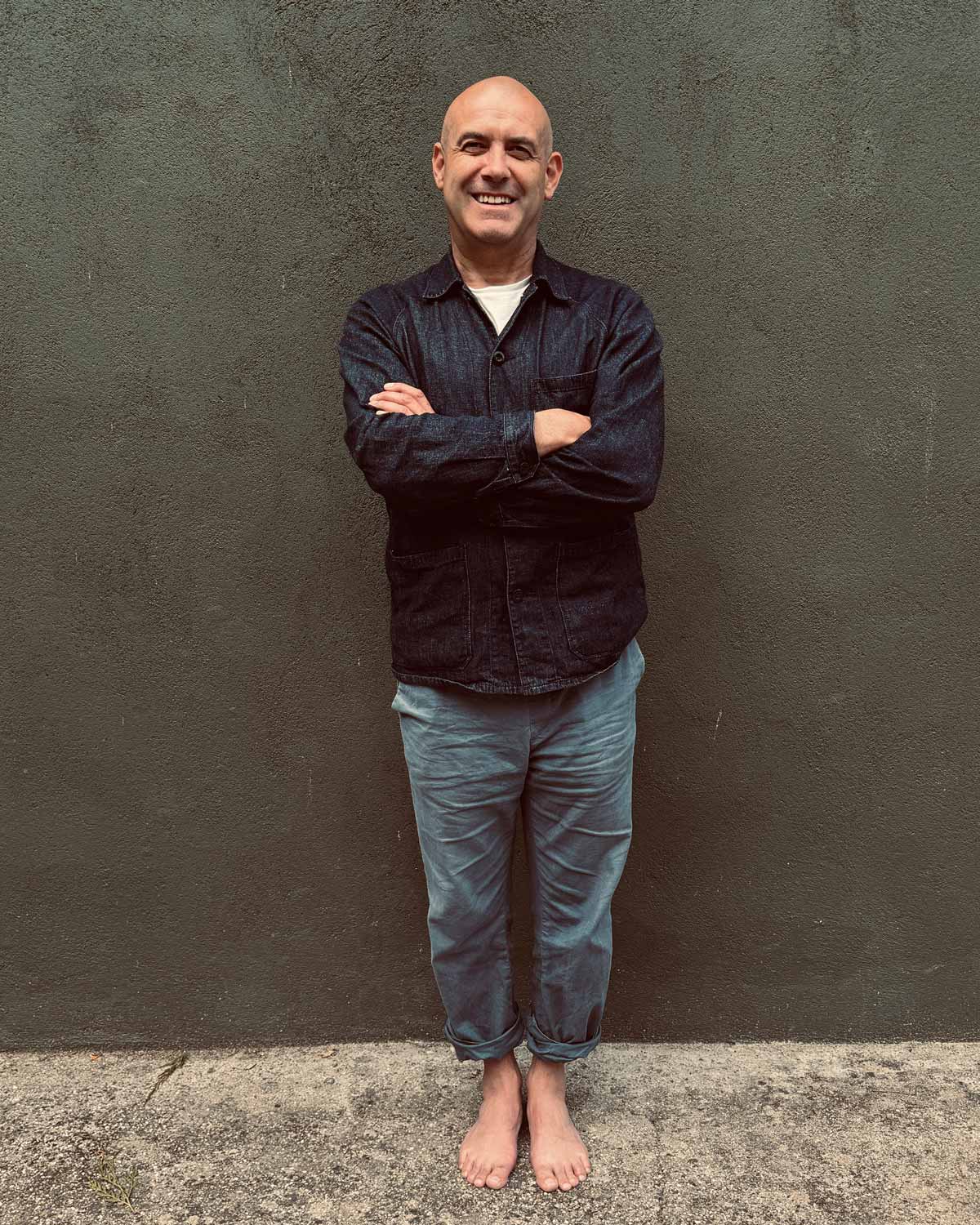

David Quinn (b. 1971) is an Irish artist known for his small-format, abstract and minimalist paintings. He considers his works, which he describes as visual haikus (a traditional Japanese form of poetry consisting of three lines with five, seven and five syllables), to be reflections on the transience of time and an expression of his meditative creative process.

In this interview, I spoke with him about his career, the influence of Eastern philosophies on his art, what excites him about curating exhibitions, and the concept of intentionlessness in his creative process.

David, thank you for taking the time for this interview. You once mentioned that you originally had no intention of becoming an “artist”, yet you have been successfully exhibiting your works for over 30 years. Can you tell us how this came about?

I studied Visual Communications, for four years, with a view to being a designer, or a photographer, but I wasn’t very good at sticking to the briefs we were given. In hindsight, I realize now, I was already thinking more like an artist than a designer, as my main interest was in the creative act itself and where it might lead, rather than a pre-determined outcome.

As Rilke said, being an artist is not really something you choose, it’s more like you can’t do anything else, or you’re miserable. My wife calls it, ‘an affliction’.

How has your work developed over the years? Were there certain phases or turning points that had a strong influence on you?

It’s hard to say, but definitely becoming interested in Buddhism and meditation had an impact. At one stage I made much wilder, bigger, chaotic paintings. I tend to think in terms of exhibitions and each one is quite different from the previous, reflecting different emotions and outside influences. As Picasso said, it’s just another way of keeping a diary.

As Rilke said, being an artist is not really something you choose, it’s more like you can’t do anything else, or you’re miserable.

Many of your works are characterized by the repetition of lines, dots and grid patterns. What role does repetition play for you?

It helps to ground me. I often think of my grandmother, who spent most of her later years, knitting traditional Irish Aran hats, sitting about six inches from the Superser gas heater, about to catch fire, with a cigarette in her mouth, and the un-tipped ash perfectly balanced, right the way down to the filter. She was a devout woman, at peace with the world, and herself, and perfectly occupied.

In addition to your artistic work, you also curate exhibitions, such as the current show ‘lucent’. What excites you about bringing these projects to life?

When I was a teenager, I loved making mixed cassette tapes. I would sit by the radio/casette player with my fingers on the PLAY/RECORD/PAUSE buttons ready to release the PAUSE one, when the song I wanted, came on. It was an art. When I had made my tape, I would take out the printed insert, (the best were BASF) and design my own cover.

Curating exhibitions, is like that, but with the adding bonus, of often getting to meet the artist, and introducing them to each other. Actually, that part of it, has been the most enjoyable aspect of ‘lucent‘.

Take us into your studio. How do you start a new work, and how do you know when one of your works is finished?

I try to work on as many pieces at the same time as possible. That way they feed off each other, and I don’t get too precious or hung up on one. Sometimes it can be hard to know when a piece is finished, and I have worked over pieces, that in hindsight, I should have let be.

It’s an occupational hazard. Like with so much else in art, it’s just an instinct. It works, and that’s it. It helps to put work away for a while, so that when you pull it out again, you are not so emotionally connected to it, and can judge it with more of a cold eye.

You said in an interview that you meditate every morning. How did you get into meditation, and how did it influence your artistic process?

I have been drawn to Eastern philosophy and aesthetics since I was very young. In my twenties and thirties I spent a lot of time with a group studying Tibetan Buddhism (although aesthetically I was more interested in Japanese Zen) and practicing meditation. I drifted away from them, as I grew older and became skeptical of some of the teachings, and the more cultish aspects of the group.

Ultimately, the highest teachings are actually very simple, and the basic techniques of meditation are useful. It’s a good way to cultivate a state of relaxed concentration, which is good for creative work. But I find now, that the way I work, is itself a form of meditation, so I no longer have a regular ‘meditation’ practice. Also, I find listening to good music, reading poetry (I am reading a lot of Rumi lately), and walking in the woods, with our dog, equally conducive to a creative state of mind, in fact sometimes more so.

It helps to put work away for a while, so that when you pull it out again, you are not so emotionally connected to it, and can judge it with more of a cold eye.

What role does the concept of intentionlessness in the creative process play for you?

I think playing around, just for the sake of it, is an excellent place to start or sometimes finish.

Looking back on your work and your journey as an artist, is there anything you would say to your younger self?

‘It’s a long road that has no turning’ – enjoy the journey.

Thank you very much, David!

More about David Quinn

https://www.davidquinn.ie/

https://www.instagram.com/davidquinn.ie/

Aesence Feature: David Quinn – Art As A Marker Of Time