Until the beginning of the 20th century, art served primarily as a mere representation of reality. In the course of modernism, however, artists began to question the conventional boundaries and definitions of art and to break away from traditional forms of expression. This led to an increasingly abstract depiction of reality and diversity. Moreover, art increasingly acted as an (often introspective) tool for the artist to explore meanings and ideas that went beyond purely physical appearances.

The fascinating thing is that the more complex the underlying themes and ideas became, the more reduced and abstract the artistic style of many artists became. And those reduced and abstract forms of expression were then, as now, the subject of controversy and misunderstanding. But how did this transformation occur? How did a representation of reality become a representation of one’s own inner world? To consider all the influences of that time would go beyond the scope of this editorial (such as the influences of prehistoric art and non-Western art at that time – more on this in this article). Therefore, in this editorial I would like to focus on the intellectual and spiritual influences.

So to understand what artists of this time, as well as today, want to express, it is important to move beyond a purely superficial examination of these artworks.

A new reality

From the beginning of the 20th century, the art world underwent a profound transformation, characterized by the search for new modes of expression and a departure from traditional forms of representation. As I explored in detail in one of my recent editorials (“From Figuration to Abstraction: Transformation of Modern Sculpture“), this period is marked by a fundamental change in artistic understanding. Influences such as psychoanalysis and new philosophical and spiritual movements like theosophy and anthroposophy found their way into art. Artists like Hilma af Klint, Wassily Kandinsky, and Kazimir Malevich began to use colors and geometric forms not only with aesthetic qualities but also with deeper, symbolic, and philosophical meanings.

Hilma af Klint, a pioneer of abstract art, was one of the first artists to integrate the teachings of these spiritual views into her art from 1906 onwards. Her paintings, often large in scale and intense in color, reflect her engagement with these esoteric theories. Af Klint believed that abstract art could communicate universal, spiritual truths. This led her to develop a language of symbols and forms that contained both mathematical and mystical elements.1

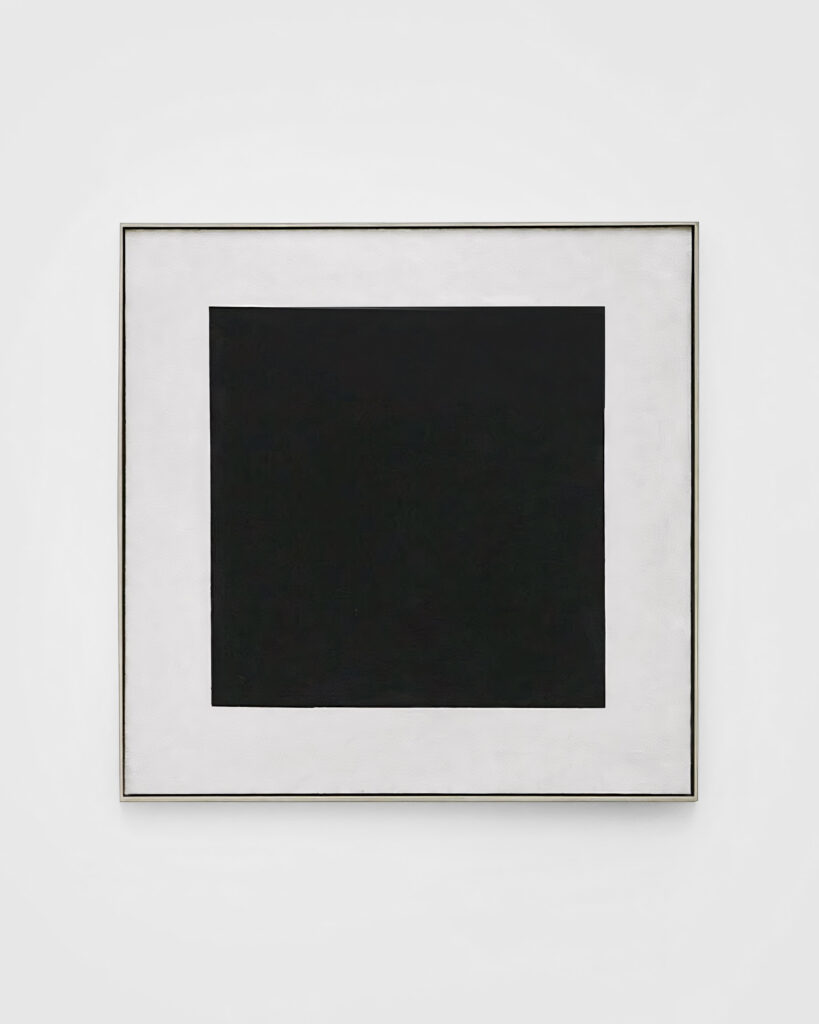

Wassily Kandinsky and Kazimir Malevich followed similar paths. In his publication “On the Spiritual in Art” (1911)2, Kandinsky emphasized the importance of the immaterial and saw art as a bridge to the exploration and representation of the unconscious. Malevich, the founder of Suprematism, on the other hand, created a radically reduced work with his “Black Square”. He saw abstraction as a means of detaching himself from the material world and reflecting on spiritual experiences. Piet Mondrian’s Neoplasticism, which used basic elements of horizontal and vertical lines as well as primary colors, also aimed to express universal harmonies and order.3 As he used to say at the time: “To approach the spiritual in art, one will make as little use as possible of reality, because reality is opposed to the spiritual.”

From spiritual to philosophical explorations

In the 1930s and 1940s, many artists and intellectuals fled to the United States to escape the rise of fascism and National Socialism. New York City thus became a center for a large number of influential European artists and thinkers.

After the Second World War, many artists sought new ways of expression to deal with the traumatic experiences of war and the rapidly changing socio-political reality. Whereas previously esoteric themes had often been central, the focus now shifted more to the artist’s inner world and more complex issues. Some, such as the Abstract Expressionists, focused on the expression of emotions. Techniques such as action painting, which is characterized by spontaneous and dynamic movements in the application of paint, were used by artists such as Jackson Pollock as a means of exploring psychological and emotional landscapes.4

Mark Rothko was also concerned with emotions. He aimed to express profound human emotions such as tragedy, ecstasy and doom through his paintings and to move people to tears. For him, art was not only an aesthetic expression, but also a form of communication between him and the viewer.5

In the 1950s, however, Eastern philosophies such as Zen Buddhism and Taoism increasingly became the focus of many Western artists.6 Agnes Martin, Ad Reinhardt and other artists explored concepts such as emptiness and silence in their works. This philosophy brought a new dimension to the art world, in which the focus was no longer only on the artwork itself, but also on the viewer’s experience of contemplation and inner reflection.

The artists of the Minimal Art movement in the 1960s around Donald Judd, Tony Smith and others were also more concerned with how the exhibited works were perceived by the viewer. Unlike the Abstract Expressionists, however, the artists of the Minimal Art movement emphasized objective observation and the physical characteristics of their objects.

Minimalist art as a tool

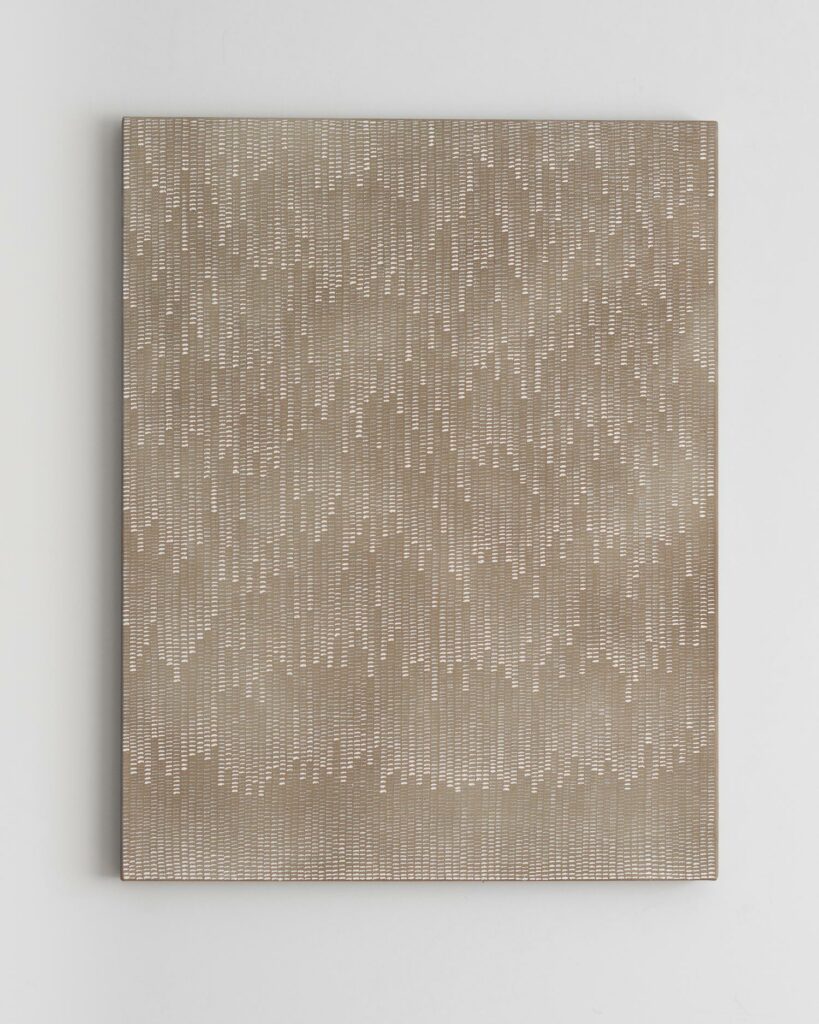

And even today, many contemporary artists with a minimalist aesthetic, such as Antonia Ferrer, Cindy Leong, Morgan Stokes or David Quinn, explore a wide range of profound topics that often intertwine aspects of the essential, the ephemeral or human perception.

They deal with the simplicity and essence of nature, fleeting moments of life, as well as materialistic and immaterial reality. They use various techniques and approaches to convey emotions or memories. This ranges from monochrome depictions to complex layering of texture and color or repetitive brushstrokes. These artists strive to promote both a meditative and introspective engagement with the human experience and the world around them through their work.

So how did the depiction of reality become a depiction of introspective and philosophical explorations? The change began with the need of those artists to go beyond the visible and explore deeper meanings and aspects of human experience. Initial influences from spiritual and philosophical ideas led to a liberation from traditional forms of representation and opened up the space for abstract and reduced forms of expression. Pioneers of abstraction, such as Hilma af Klint, Wassily Kandinsky, and Kazimir Malevich, laid the groundwork by ensuring that their works were understood not merely as aesthetic decorations, but as expressions of deeper, often immaterial meanings.

Throughout the 20th century, this abstract and non-objective art became increasingly introspective – it became a medium for exploring and communicating the artist’s inner world of thought. It has become a powerful tool for exploring existential and philosophical issues. Or as the contemporary artist Alicja Kwade herself says so aptly about her work: “I am probably dealing with the same questions as philosophers, but we express ourselves in a different language.”7

Further Reading / Resources

- https://www.guggenheim.org/teaching-materials/hilma-af-klint-paintings-for-the-future/science, https://www.bildmuseet.umu.se/en/exhibitions/2004/hilma-af-klint/

- https://www.csus.edu/indiv/o/obriene/art206/onspiritualinart00kand.pdf

- https://www.theartstory.org/movement/neo-plasticism/

- https://www.nytimes.com/1992/05/31/nyregion/art-pollocks-psychoanalytic-drawings.html

- https://www.moma.org/artists/5047 , https://www.nga.gov/features/mark-rothko.html

- Romina Dümler, Barbara Könches, Meeting the Monochrome ZERO and Dansaekhwa, S.11 ff

- https://www.artdependence.com/articles/i-am-probably-dealing-with-the-same-questions-as-philosophers-but-we-express-ourselves-in-a-different-language-an-interview-with-alicja-kwade/