In the latest edition of our interview series, we once again dive into the world of minimalist aesthetics. In inspiring conversations with creative minds from the fields of architecture, design, and art, we explore how they are guided by their vision and how they express it in their works. Along the way, they provide us with interesting insights into their creative process and reveal how they perceive and shape the world. This time, I had the pleasure of having an inspiring conversation with German designer Dirk Winkel.

Dirk Winkel is a Berlin-based product designer whose work is characterized by the principles of formal purism. His focus is on lighting and furniture design, and he is particularly known for exploring the boundaries of industrial production processes and innovative materials.

In this interview, Dirk Winkel talks to me about his design philosophy, how he finds the balance between technological innovation, function and aesthetics, and gives inspiring insights into his versatile design process.

Dirk, thank you for your time! Please tell us how you would describe your personal design philosophy and aesthetics. How has it developed over the course of your career?

Essentially, my reduced design language, which is oriented towards basic forms, is always based on the idea of giving a clear framework to an underlying technical principle, innovation, or novelty, so that the focus is entirely on the actual idea behind it, far from any styling. This aesthetic rigor is therefore never an end in itself. What might have changed somewhat is my initial approach of wanting to show every constructive detail externally; nowadays, I feel a bit freer and less dogmatic in this regard.

You are driven by the idea of formal purism as a basic principle of sustainability. How do you personally define this principle, and what do you think are the key elements that make a design timeless?

I am convinced that a sustainable design involves more than just the materials, processes and product cycles. Only when we free ourselves from fashions and fleeting trends can a design become lastingly valid. A chair, for example, that is passed down from generation to generation instead of being recycled will always be the most sustainable solution. This requires a great deal of self-criticism and restraint in the design process to arrive at a convincing solution in terms of form.

Only when we free ourselves from fashions and fleeting trends can a design become lastingly valid.

Your designs are incredibly innovative and aesthetic at the same time. How do you find the balance between technological innovation, function and aesthetics?

Typically, the technical parameters underlying the innovation determine the proportions and dimensions, for example, the power of a lamp dictates the size of the optical components and the heat sinks. It is never a simple matter of “packaging” the technology into a shell, but rather both mutually influence each other. Each radius, each proportion must be carefully considered here.

You place great emphasis on exploring new materials, as the “winkel w127” impressively demonstrates. Please guide us through your typical design process, from concept to finished product. How significant is the role of research and development in your daily work?

The process from being inspired by a new material or technology to the finished product never follows the same path. In the case of the w127, various detours, material changes, and experiments were involved, as the entire manufacturing process was an untested venture at the time, which is still appreciated by the lovers of the design today.

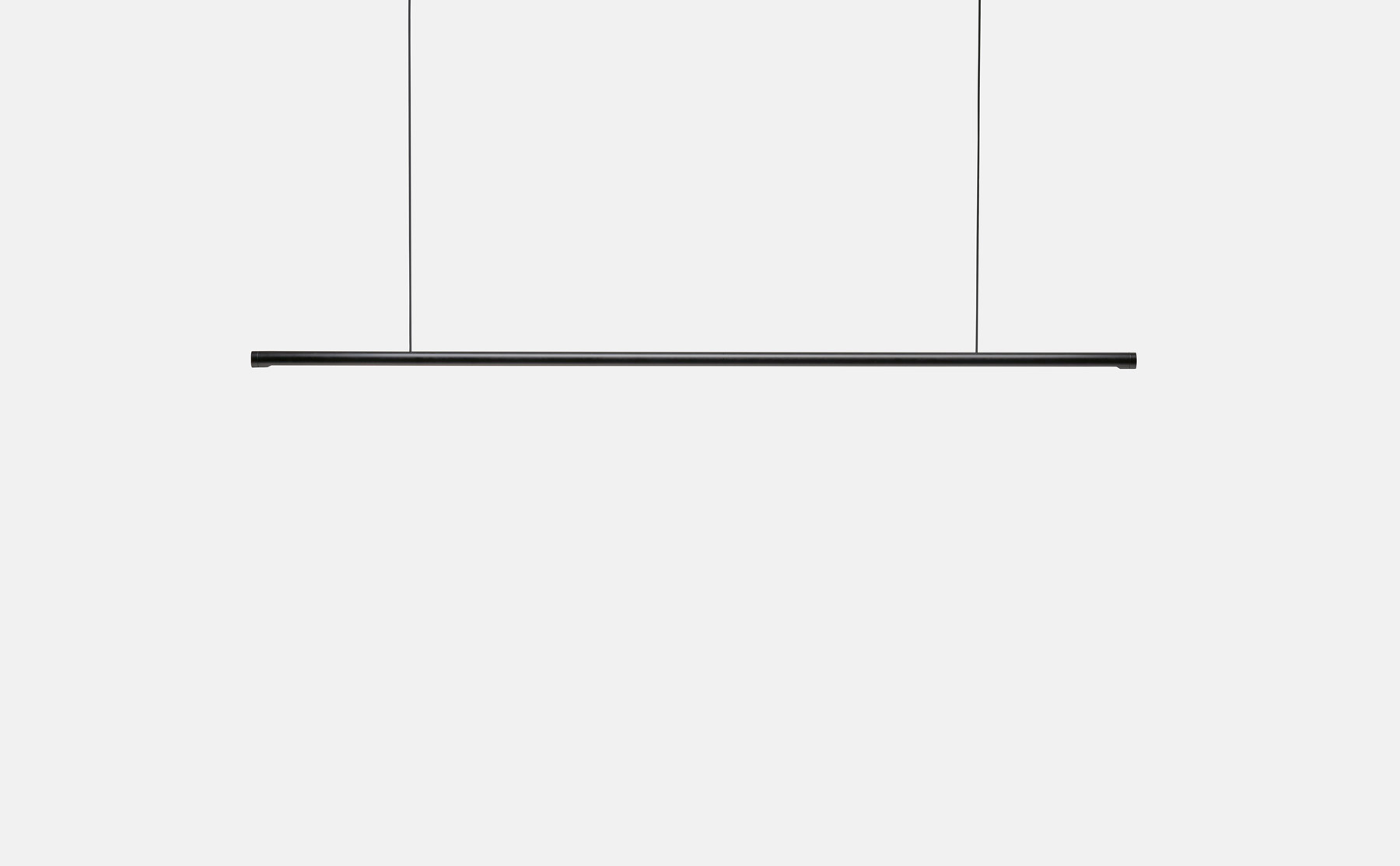

In contrast, designs like the w181 ‘Linier’ followed a very straightforward process, as it was more a light-technology challenge that could be resolved quicker. Research and experimentation are always deeply rooted in my work, both in research and in model making, and often form the basis of the dialogue with the subsequent manufacturer.

How do you assess the current state of the design industry in terms of environmental sustainability? What do you think designers or companies should do to drive positive change?

Remarkable progress has been made in the last two decades, whether it’s in the development of new materials, processes, or product lifecycle concepts. The constant question is, what should be achieved? It requires entrepreneurial courage to introduce the public to something that breaks away from traditional expectations, perhaps by foregoing elaborate finishing and painting, but this also brings the opportunity to lead the way. Designers should also challenge manufacturers in this regard.

You also pass on your knowledge as a lecturer/guest professor at universities. How does your teaching influence your practical work as a designer and vice versa?

Teaching brings with it the little luxury of being able to look into the creative minds of another generation and learn what currently moves and occupies them. So it is always a dialogue from which both sides can learn something. In my everyday work, for example, this could be the inspiration for a new typology based on new life models, the requirements of which I only became aware of during the teaching process.

Teaching brings with it the little luxury of being able to look into the creative minds of another generation and learn what currently moves and occupies them.

What defines good design for you?

Here I’ll stick to Rams’ ten theses without any hesitation, and then emphasize number 10 again: Good design is as little design as possible.

How do you see yourself and your work in the future? Are there any specific projects or materials that you haven’t worked with before but would like to try?

I started my career with a particular focus on lighting and luminaire design, and this will always be very much part of my work in the future. At the same time, however, I find it increasingly exciting to move in the context of ‘new work’ and to think about the ways in which work and life will be related in the future.