In the latest edition of our interview series, we once again dive into the world of minimalist aesthetics. In inspiring conversations with creative minds from the fields of architecture, design, and art, we explore how they are guided by their vision and how they express it in their works. Along the way, they provide us with interesting insights into their creative process and reveal how they perceive and shape the world. This time, I had the pleasure of having an inspiring conversation with Liam Stevens.

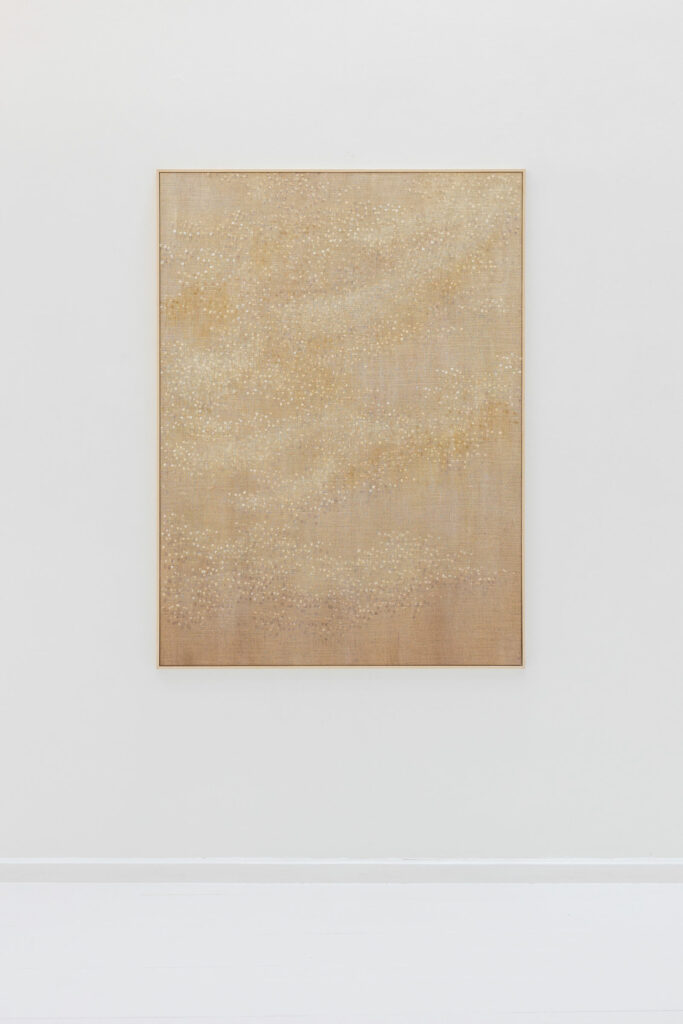

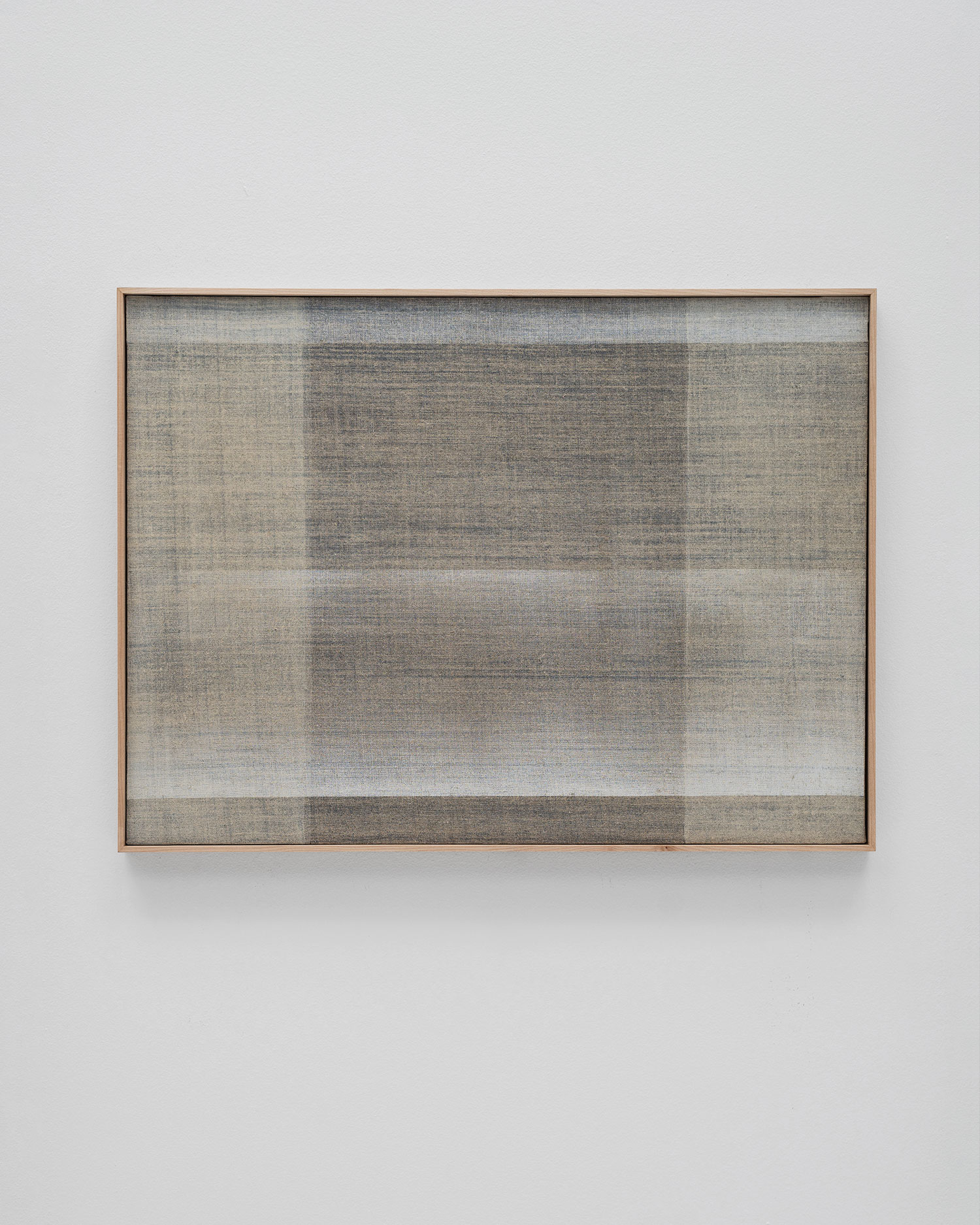

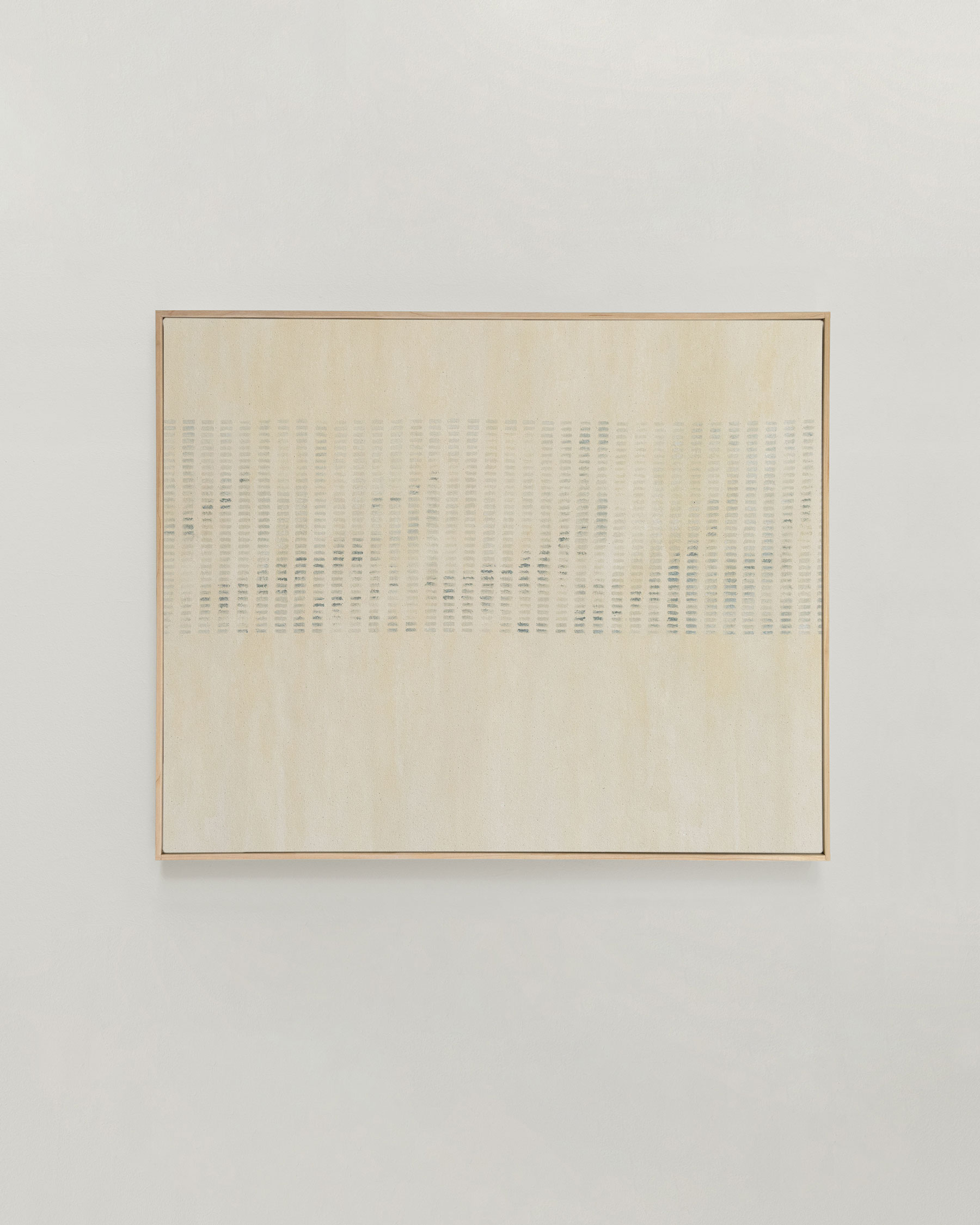

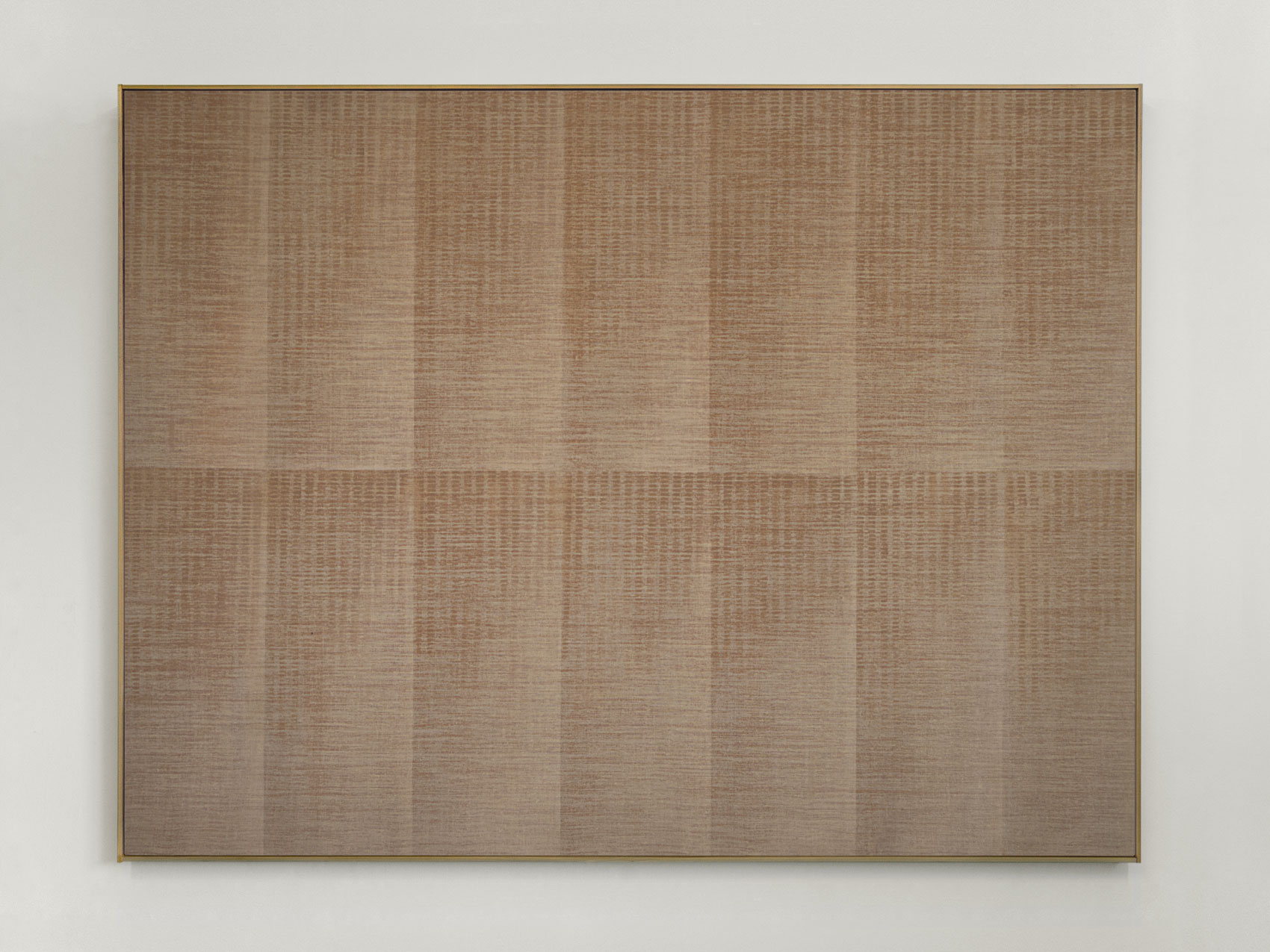

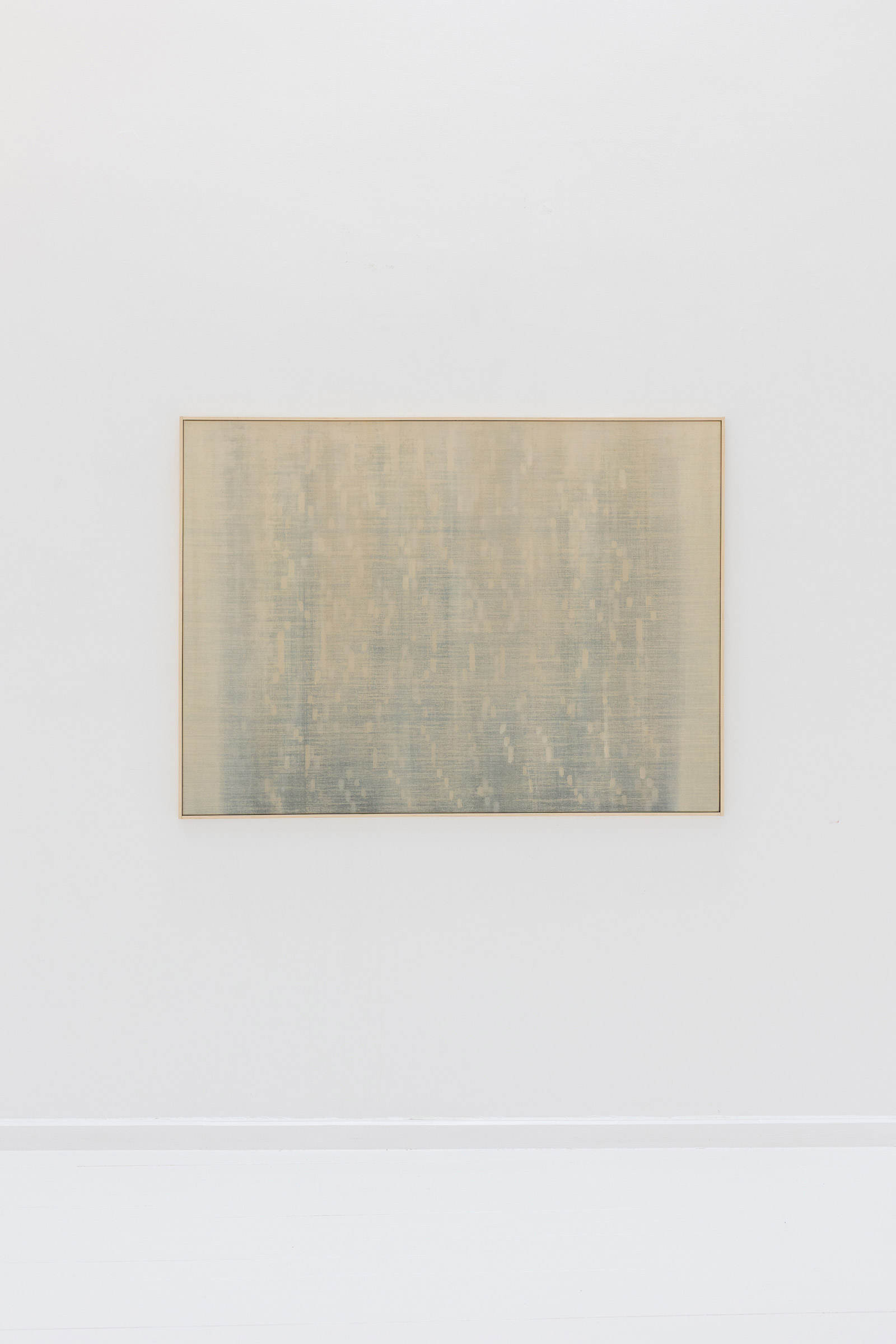

Liam Stevens (b. 1985) is a British artist whose abstract works are characterized by a minimalist aesthetic and a subtle color palette. Using pencil and acrylic pigment and a methodical creative process, Stevens creates reduced compositions that radiate a meditative calm. Through the repetition of lines, grids and clusters, his works invite the viewer to pause and engage with the subtle nuances that only become visible on closer inspection.

In this interview, I speak with Liam about his journey to becoming an artist, the importance of repetition and structure in his works, as well as his methodical yet intuitive creative process. He also shares insights into his current exhibition “Eventide” at the Alzueta Gallery in Barcelona, which focuses on transitions and cyclical time, and his plans for his new workspace in the mountains of western Tokyo.

Liam, thank you so much for your time! Please tell us how your artistic journey began. Was there a defining moment that led you to become an artist?

Thank you very much for having me. Finding this path ultimately took time, reflection, and a lot of push-and-pull with my environment as I refined my direction. I grew up drawing a lot. My father was once a technical illustrator, and we would spend weekends sketching and painting as children. We had lots of art books in the house, and when I moved to London almost 20 years ago, I frequently visited all the major galleries to see shows. I still do. It has always felt natural. I suppose my father drew pictures for a living, so that seed had been sown in me from early on, but took a while to mature.

After initially working in illustration and design — I was with The World of Interiors magazine as an art editor/designer for well over a decade — the journey to becoming a painter was incremental, guided by what felt truer to my sense of self as I grew older. Painting became the ultimate truth for me. Following this path isn’t always about production in a material sense. A lot of it, especially at the beginning, involves wrestling with introspective ideas that lead to many different trails of thought. Exposing myself to different philosophies helped give myself permission to pursue painting.

How would you describe your art to someone who has never seen it before?

I often find descriptions limited in reach, as words create a mental picture that is uniquely specific to the person who hears or reads them. I sometimes find that side of art writing a bit restrictive. I seem to recall Howard Hodgkin once remarked that a description distinctly comes between the viewer and the work. He felt that attaching an explanation could lead the viewer to look for something they may never find. The best scenario is to simply view the work and respond to the experience of it.

Though concepts can be outlined in words, the visceral response to a work—its scale, color, and composition—can only truly be felt by looking at it. However, so much art is consumed via social media or online, and the connection and experience with the work, particularly its scale and light, can never be fully grasped on a screen.

That said, if I were to frame a description based on words borrowed from viewers, I might suggest balance, repetition, and perhaps calm.

Exposing myself to different philosophies helped give myself permission to pursue painting.

Repetition always plays a central role in your works—be it in lines, forms, or geometric patterns. What fascinates you about the idea of repetition?

Repetition is life in all its aspects. There is nothing abstract, conceptually, about repetition. Everything in this universe is categorized by pattern. It is everywhere—from human design in panes of glass or brick to ripples in the canal, geological layers, leaves on a tree, cells in our bodies, days of the week, sleep, and the cyclical nature of the seasons. It is the reality we experience at every moment, and my work reflects conditions of that reality.

Within this, I have always tried to combine elements of the human-made with motifs or processes that elicit some connection to nature and the world we inhabit, affirming the idea that we are not separate from nature but come from it.

Your creative process is very methodical—you stain each canvas up to 30 times with pigment washes. Can you tell us more about your process? How do you start a new work, and how do you find the balance between simplicity and complexity?

In the beginning, the repeated staining was a mantra-driven process. The slow build-up of layers compressed time into each piece. I still work like this, but now it is more about continuing until the work feels complete rather than adhering to the original philosophy of marking time in the process. I have also started using other materials that respond to staining and paint in different ways, so I adapt the process to suit each type of work.

While some works bridge ideas of space within the frame, the work exists in the material, so the materiality of painting—the finish and surface—is important to me. It is an object. Over the years, my works have become more complex as different ideas and processes are explored, but I don’t have any hard rules for the work at large. Intuition and feeling guide the outcome.

While some works bridge ideas of space within the frame, the work exists in the material, so the materiality of painting—the finish and surface—is important to me.

In relation to your series “Array,” you once spoke about how self-imposed constraints help you deepen the themes within your practice. Have these constraints always existed in your work, and how important is the process of letting go in this context?

Constraints ultimately tie back to the idea of pattern and repetition, where the visual components within the work are often confined without a strong hierarchy in size or scale. This creates an initial set of rules for the composition, where the constituent parts are equal to some degree. In the Array series, the arrangements are entirely tied to an array of marks. At the moment, I am evolving this approach visually, where the array is fixed within its own grid, but the placement of that grid remains fluid and free of constraint.

Juxtaposing opposites—such as ruled lines or ordered shapes with flowing washes and the imperfections of layered, wet paint—feels symbolic of the exchange between intention and chance, much like the way nature and the human-made interact in our environment. I’ve always been drawn to multiplicity in this way: light exists only with darkness, sound only with silence. Balancing a structured, ruled plan with the unpredictability of chance in the process creates something layered and unique for me.

What do you hope viewers take away from your art? Is there a certain feeling you want to evoke when looking at your paintings?

The work is a result of my own feelings; I am pursuing ideas that hold personal significance for me. In my mind there is a fluid, shifting image—or type of ‘static’—that drifts and surfaces from within the depths of my consciousness. Flashes of it in different forms often create an image or a ghost of an image. Perhaps it reflects the many iterative forms and patterns that are subconsciously absorbed day to day. Painting for me is the only way I can express it and perhaps resolve or process it somehow.

I also believe these images are attached with an emotional weight, so when I focus on this experience, it usually has an emotional effect on my mind. The methodical creation of the work is a way of making this abstract thought tangible in real space. If the work resonates with the viewer, then I suppose, in some way, I am less alone in my own perspectives as an image-maker, and I deeply respect that connection. But how the work is perceived is outside of my control. I can only make the work; I cannot, nor would I wish to, direct what feelings it generates in someone else – though I hope it reveals something positive. The world needs more positive energy.

You are currently having a solo show at Alzueta Gallery Turó in Barcelona entitled “Eventide.” Congratulations! What works are you displaying at the show, and what is it about?

Thank you! These works represent the culmination of a recent exploration into new materials and a more conceptual approach within my practice. Themes of transition, shifting light, and the cyclical passage of time remain central to my process. Most of these works were painted during the seasonal transitions from late summer to early winter, as the days grew shorter and the evening light in the studio changed incrementally.

The new Drift series in the exhibition explores fractal geometry and time, using panels as sequential “frames” while extending repeated forms, mirroring self-similar patterns found in nature. My studio practice occasionally incorporates computer-based sketching, generating visual ideas that parallel early programming, such as the Jacquard loom and Hollerith code. For me, these references recall early human visual perception—how the brain begins “programming” the eyes for complex stimuli even in the womb. It’s thought that our earliest visual experiences are patterns of light and dark, perhaps something like “static.” I see the pixel-like repetition and static in my work as a bridge between nature’s patterns and human design.

Balancing a structured, ruled plan with the unpredictability of chance in the process creates something layered and unique for me.

What are your plans for the future? Are there any topics or ideas you would like to explore further?

Currently, I am renovating a studio space in the mountains of West Tokyo prefecture. I have been travelling between Japan and the UK for over 20 years now, and I wanted a space to work while staying connected with family in Tokyo. Renovating overseas has been a long process—being primarily based in London has meant things have progressed quite slowly—but this year, it will finally be up and running… I hope.

Spending time between these two places has long informed my practice. Eastern philosophies, particularly the concepts of Ma and Li, have had a direct impact on my work. Ma refers to the space between things—not simply emptiness, but an intentional and meaningful negative space that shapes perception, rhythm, and interaction. This sensibility influences how I approach composition, balance, and absence within my paintings. Li, on the other hand, is the principle of organic pattern and natural order, seen in everything from wood grain and flowing water to the repetitive structures of rock formations and tree branches. These recurring forms in nature, shaped by time and imperfection, are fundamental to the way I think about repetition and movement within my work.

Moving forward, I want to continue developing my work in response to the forests, rivers, lakes, and mountains surrounding my new studio in Japan. Even in the short intervals I’ve spent there during renovations, I’ve been overwhelmed with ideas. The landscape is truly beautiful, and I look forward to seeing how it weaves itself into my paintings.

Thank you very much, Liam!